|

Not Me, Mate! - Why People Deny Responsibility When Under Threat

|

Recently, I had some renovations done, and as usual, some unanticipated mistakes arose. When I spoke to the first tradie, his immediate reply was, "Not me, mate. It was so-and-so." So, I approached 'so-and-so,' another tradie, and his response was exactly the same: "Not me, mate. It was the first guy."

This dynamic went round and round for about two months until I organised (maybe demanded? lol) a tête-à-tête with both. I asked them for a solution, but both were preoccupied with telling the same old story: "Not me, mate." I asked them to stop mentioning what had happened and focus only on solutions. Within a minute or two, a solution was found.

"Not me, but you" is a defence response. It means we feel under threat.

This situation reminded me of something I often see in sessions. Whether it’s in personal, social, or professional relationships, it’s the ‘not me, it’s you’ response, usually followed by finger-pointing. People can waste a lot of time—sometimes decades—in this no-win practice of blame.

Whenever I encounter this problem, I keep returning to one question, especially if I hear the same words coming from my own mouth:

What makes it so difficult for us to consider that we might have made a mistake?

In these situations, those involved often rely on their memory for proof of the facts: "I didn’t …," "you always …," "it was a Tuesday …," "I couldn’t have because I was somewhere else …" But if you take a minute to browse the research on memory, you’ll quickly see it’s probably our most unreliable cognitive ability. We tend to remember things that are attached to strong feelings, and everything else is forgotten. Yet, in situations where a mistake is identified, we insist our memory is perfect, faultless.

In these situations, those involved often rely on their memory for proof of the facts: "I didn’t …," "you always …," "it was a Tuesday …," "I couldn’t have because I was somewhere else …" But if you take a minute to browse the research on memory, you’ll quickly see it’s probably our most unreliable cognitive ability. We tend to remember things that are attached to strong feelings, and everything else is forgotten. Yet, in situations where a mistake is identified, we insist our memory is perfect, faultless.

One of the best examples of our flawed memories and difficulty in owning up to a mistake comes from a writer, not an academic. Mary Carr is a New York Times bestselling writer who teaches memoir writing at Syracuse University. Each semester, she stages an argument between herself and another professor in front of her class, secretly video-recorded. After the argument, she first asks her students, as an exercise in writing memoirs, to write down what they observed. It’s rare for a student to remember the true facts. Most attribute the wrong words to the wrong person, can’t remember how it started or finished, and some even suggest the opposite of what was said. What’s even more astonishing is that after she reveals the staged nature of the argument and shows the video, some students still hold to the belief that their version is true and that the video has been tampered with!

Why do people deny responsibility when under threat?

‘Not me, but you’ is a defence response. It means we feel under threat. Under threat, our cognitive abilities—problem-solving, decision-making, comprehension—are diminished. No organisation can function effectively without robust relationships, and problem-solving is crucial to daily functioning.

Take a minute. Is it possible that you can’t really remember every specific detail? Maybe the mistake was partly yours?

This approach seems logical – but how do I embed this in my work team? How do we get buy-in on this attitudinal approach?

People forget things all the time, yet in situations where a mistake is identified, we tend to insist that our memory is perfect.

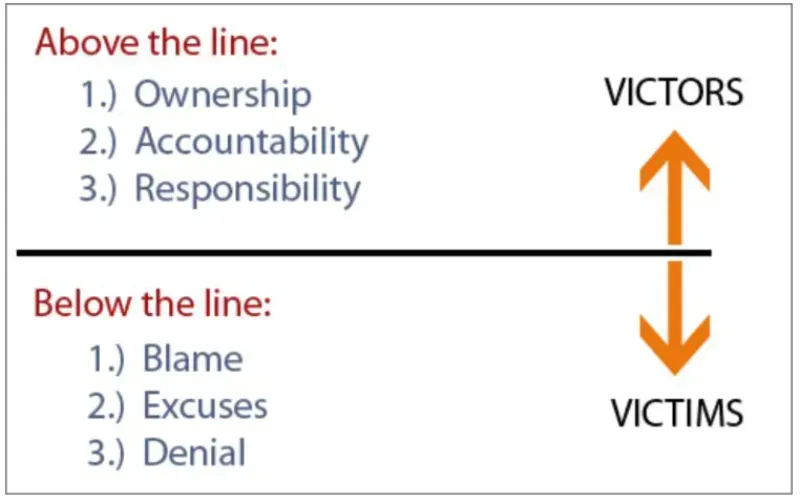

At Purpa, we love the simple framework of operating “above the line” versus “below the line.” When faced with any scenario in business or our personal lives, we can respond (rather than react). This framework is easy to adopt, can be communicated clearly, and most importantly, gives everyone in your team ‘permission’ to set the expected team standards.

So, if everyone shifted from an automatic response of ‘not me, mate’ to ‘how can I solve this,’ what would that do for your business?

Clive is our Psychologist. With over 40 years of experience, Clive helps business people navigate through the complexities of change. Key to his work is a fundamental belief that life is change and, in this respect, most of his career has focused on identifying the key aspects of the change process.